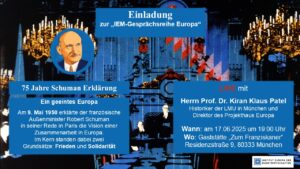

Speeches and discussions took place in Guadalajara Mexico between entrepreneurs and bishops as a contribution for South America’s strife for new forms of economy and state. The IEM contribution was about the Social Market Economy in the 21st century.

Many countries in the region have seen people’s anger explode – an explosion with an announcement.

Is Latin America sliding into chaos? For weeks, students and the police have been fighting each other on Chile’s streets, demonstrating against the government and the „system“. After all, opposition and government have now agreed on a way for a new constitution. When a few weeks earlier tens of thousands of mainly indigenous demonstrators stormed the Ecuadorian capital Quito because of a gasoline price increase, President Piñera boasted that this could never happen in Chile. Even Bolivian President Morales, who had fled to Mexico, did not expect at the time that his fraudulent re-election would cause such turmoil among the people that the army would recommend his resignation. Everything is in a state of flux: in Peru new elections will take place after the dissolution of parliament, in Argentina a left-wing government has replaced a liberal one, in Uruguay the opposite is likely to happen soon. The crisis in Venezuela has almost fallen into oblivion, but thousands continue to flee from hunger and dictatorship every day.

Latin America is a powder keg. One wonders in which country the next explosion will take place. The triggers of the protests differ, but the starting point and the historical stage that the countries in the region are going through are similar. Latin America has never undergone deep structural change; industrialisation has only begun. The economy is based on the export of raw materials. Copper, oil and soya have been added to gold and coffee, lithium and rare earths will soon be added.

Socially, the feudal system of rule has survived. To this day, a small, wealthy elite has great economic and political power. This elite allied itself with military dictatorships and even with socialist governments to protect its interests. Where other groups reach for the riches, new elites emerge who are equally concerned with maintaining power – also by force, which is still a means of politics today.

Neither liberal consolidation policies nor leftist redistribution have changed anything about inequality in Latin America. But something decisive has happened in the past two decades: The rise of China has caused demand for raw materials and their prices to rise sharply. Commodity exporters experienced an unprecedented boom. Their coffers were fuller than ever before. But in Latin America’s typical quest for immediacy, governments hardly invested in the future, but in the present. Redistribution programs and cheap jobs turned millions of poor people into consumers. In the huts of the Brazilian favelas there are large television sets today, all parking spaces in front of the universities in Chile are occupied, in Bolivia’s El Alto there are the showy houses of indigenous climbers.

But the problems have not diminished: public schools, hospitals and means of transport are still in a miserable condition. The emergence of a „new middle class“ was a myth. Social security continues to exist only for the wealthy. Those who are poor generally remain so. A relapse into poverty constantly threatens to rise. Economically, the region has remained dependent on the export of raw materials. When the boom came to a halt a few years ago and the economies in Latin America no longer achieved the growth rates needed to maintain consumer power, the rush came to an end. Expectations and hopes could no longer be fulfilled. It was a small step from disappointment to anger. All over Latin America, frustration is now unleashing itself. The anger is directed against the political class. It doesn’t matter whether the country is governed from the left or from the right.

Actually, the current events in the region were foreseeable. It had precursors: In Brazil years ago, a spontaneous protest movement emerged apparently out of nowhere, which the political class had chosen to blame. Other factors increase the anger of the citizens. In Brazil it was a massive corruption scandal that came to light. In Bolivia it was the self-assertion of President Morales that led him to commit electoral fraud; in Chile it was the obvious ignorance of the president, who at the beginning of the protests thought he was in „war“.

Where Latin America is heading cannot be foreseen. The political divisions as well as the dissociation of the population from politics weaken democracy. The power vacuum that is being created is enabling figures from the political margins to rise. In Brazil, a right-wing nationalist has come to power, Jair Bolsonaro. In Bolivia, Chile and other countries, too, there are extremists left and right who see their chance coming. But they are the last to see the deep rifts in the society.